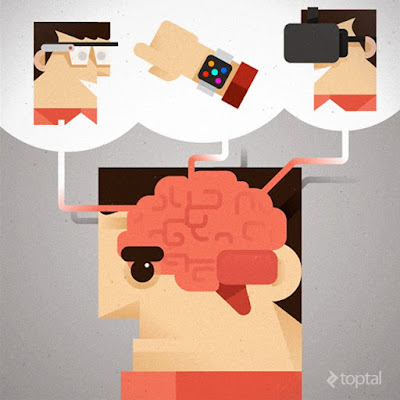

In recent years we’ve seen new, disruptive innovations in

the world of wearable technology; advances that will potentially transform

life, business, and the global economy. Products like Google

Glass, Apple Watch, and Oculus Rift promise

not only to change the way we approach information, but also our long

established patterns of social interaction.

Indeed, we are witnessing the advent of entirely new genre

of interface mechanisms that brings with it a fundamental paradigm shift in how

we view and interact with technology. Recognizing, understanding, and

effectively leveraging today’s growing landscape of wearables is likely to be

increasingly essential to the success of a wide array of businesses.

In this article, we discuss the ways in which effective

interface design will need to adapt, in some ways dramatically, to address the

new psychology of wearable technology.

Enter the Neuroscientific Approach

Cognitive neuroscience is

a branch of both psychology and neuroscience, overlapping with disciplines such

as physiological psychology, cognitive psychology, and neuropsychology.

Cognitive neuroscience relies upon theories in cognitive science coupled with

evidence from neuropsychology and computational modeling.

In the context of interface design, a neuroscientific

approach is one which takes into account – or more precisely, is centered upon

– the way in which users process information.

The way people interact with new, not-seen-before

technologies is more bounded to their cognitive processes than it is to your

designer’s ability to create stunning UI. New,

often unpredictable, patterns emerge any time a person is presented with a

tool, a software or an action that he has never seen before.

Accordingly, rather than employing more traditional approaches

(such as wireframing and so on), you will instead focus on the sole goal of

your product, the end result you want the user to achieve. You will then work

your way back from there, creating a journey for the user by evaluating the how

to best align the user’s intuitive perception of your product and his or her

interaction with the technology used. By creating mental images, you won’t need

to design every step the user has to take to accomplish an action, nor you will

have to evaluate every possible feature you could or couldn’t include in the

product.

DISCLOSURE: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning when you click the links and make a purchase, we receive a commission.

Consider, for example, Google Glass Mini Games.

In these 5 simple games made by Google to inspire designers and developers, you can see exactly

how mental images play a major role in user engagement with the product. In

particular, the anticipation of a future action comes to the user with no

learning curve needed. When the active elements of the game pop up into view,

the user already knows how to react to them and thus forms an active

representation of the playing environment without the need to actually have one

to see. Not only has the learning curve has been reduced to a minimum, but the

mental images put the user in charge of the action immediately, anticipating what the user will do and just letting the user do it.

Bear in mind that is possible to identify three different

types of images that form in the brain at the time of a user interaction, all

of which need to be adequately considered and addressed to achieve an

effective, and sufficiently intuitive, interface. These include:

- Mental images that represent the present

- Mental images that represent the past

- Mental images related to a projected potential future

And don’t worry. You don’t need to run a full MRI on your

users to test what is going on in their brain to arrive at these mental images.

Rather, you can simply test the effectiveness and universality of the mental

images you’ve built.

Users Do What Users Do

When approaching a new technology, it’s vital to

understand how users experience and relate to

that technology. In particular, a reality check is often needed to recognize

how users actually use the technology in spite of how they’re “supposed to” (or

expected to) use it. Too many times we’ve seen great products fail because

businesses were expecting the users to interact with them in a way that in

reality never occurred. You shouldn’t jump on the latest, fancier technology

out there and build (or, worse, re-shape!) your product for that technology

without knowing if it will actually be helpful to, and adapted by, your users.

This is an easy mistake and it’s quite eye-opening to see the frequency with

which it occurs.

Leveraging Multiple Senses in Wearables

Wearables bring the great advantage of being way more

connected to the user’s physical body than any smartphone or mobile device

could ever hope for. You should understand this from the early stage of your

product development and stop focusing on just the hand interaction. Take the

eyes for example. Studies conducted with wearable devices in a hands-free

environment have shown that the paths users follow, when their optical abilities

are in charge, are different from the ones you would expect. People tend to

organize and move in ways that are due to their instinctive behavior in spite

of their logical ones. They tend to move instinctively towards the easier,

faster paths to accomplish that action, and those paths are never straight

lines.

One application that effectively leverages multiple senses

is the Evernote app for the Apple Watch. Actions in the Watch version of the application have the

same goals as their desktop/mobile counterparts, but are presented and

accomplished in totally different ways. With a single, simple button click, you

can automatically access all of the feature of the app: you don’t need multiple

menus and differentiation. If you start talking, the application immediately

creates a new note with what you’re dictating, and syncs it with your calendar.

As a user, you are immersed in an intuitive experience here that lets you be in

charge of what you’re doing, while presenting you with an almost GUI-free

environment.

And what about our more subtle, cognitive senses?

Wearables bring the human part of the equation more fully into account with a

deeper emotional connection: stress, fear and happiness are all amplified in

this environment. You should understand how your product affects those

sensations and how to avoid or take advantage of those effects.

Just remember: let the cognitive processes of the users lead

and not the other way around.

Voice User Interface (VUI)

In the past, designing a Voice User Interface (VUI) was particularly difficult. In addition to all the

challenges in the past with voice recognition software, VUIs also present a

challenge due to their transient and invisible nature. Unlike visual interfaces, once verbal commands and actions have been

communicated to the user, they are not there anymore. One approach that’s been

employed with moderate success is to give a visual output in response to the

vocal input. But still the designing of the user experience for these types of

devices presents the same limitations and challenges of the past, so we’ll try

to give a brief overview here of what people like and don’t like about VUI

systems and some helpful design patterns.

For starters, people generally don’t like to speak to

machines. This might be a general assumption but it is even more true if we

consider what speaking is all about. We interact with someone taking in

consideration that the person can understand what we’re saying or at least has

the “tools” and “abilities” to do so. But even that is not generally sufficient.

Rather, speaking with someone typically involves a feedback loop: you send out

a message (carefully using words, sounds, and tones to help ensure that what

you say is properly understood in the way you intended). Then the other person

receives the message and hopefully provides you with some form of feedback that

hopefully confirms proper understanding.

With machines, though, you don’t have any of this. You

will try to give a command or ask for something (typically in the most metallic

voice you can muster!) and hope for the machine to understand what you’re

saying and give you valuable information in return.

Moreover, speech as a means for presenting the user with

information is typically highly inefficient. The time it takes to verbally

present a menu of choices is very high. Moreover, users cannot see the

structure of the data and need to remember the path to their goal.

The bottom line here is that these challenges are real and

there are not yet any “silver bullet” solutions that have been put forth. In

most cases, what has been proven to be most effective is to incorporate support

for voice interaction, but to limit its use to those places where it is most

effective, otherwise augmenting it with interface mechanisms that employ the

other senses. Accepting verbal input, and providing verbal feedback, are the

two most effective ways to incorporate a VUI into the overall user experience.

Micro-interactions

While designing for wearable tech, remember that you will

find yourself in a different, unusual habitat of spaces and interactions that

you’ve probably never confronted before (and neither have most of your users).

Grids and interaction paths, for example, are awesome for

websites and any other setting that requires huge amount of content to be

handled. With wearable devices, though, you have limited space for interaction

and should rely on the instinctive basis of the actions you want to implement

to give the best experience to the users.

Let’s take the Apple Watch for example.

For one thing, you will only be able to support one or two concurrent

interactions. Also, you don’t want the user to need to constantly switch

between tapping on the screen and scrolling/zooming the digital crown on the

side of the device. frankly, even Apple itself made mistakes in this regard. In

handling the Watch’s menu interface, for example, to safely tap an icon on the

menu, you will need to zoom-in and out most of the time using the crown while

briefly distracting yourself from the direct task you wanted to accomplish.

A great example of effective micro-interaction design can

be found in the Starwood Hotels and Resorts app for the Apple Watch. The Starwood application for Apple Watch perfectly fits

their personal brand experience by letting

users unlock their room door in the hotel by the simple tap of a button. You

don’t need to see the whole process going on to enjoy what this kind of

micro-interaction can do. You’re in the hotel and you want to enter your door

without going in your bag or pocket looking for the actual key. The app also

shows one of the best practices for wearables: the selective process. Don’t put

more actions or information that you should, otherwise it will disrupt the

experience (like in the Apple menu example). Rather, just show the user the

check-in date and the room number. When they click “unlock” a physical reaction

occurs, outside the device and into the real world.

The KISS Principle

The well known KISS

Principle is perhaps even more relevant in the

domain of wearables than it is with more traditional user interface mechanisms.

The Wishbi ShowRoom app for

Google Glass is a great working example of a light UI that enriches the user

experience without “getting in the way”. It has already been incorporated by

companies like Vodafone and Fiat. Basically, it facilitates streaming online

content live, even at different quality rates. And it does that with two simple

actions; one that helps you start the broadcasting, and a split screen that

captures everything you’re seeing. For an action as complicated as live

broadcasting, the app manages to be extremely lightweight and unobtrusive.

Wearable Technology Conclusions

Remember, every interface should be designed to empower

and educate the user to perform a desired activity more quickly and more

easily. This is true for every interface platform, not just wearables.

But that said, please DO go crazy! Wearable technology is

a revolutionary field, and even though you can look out for principles and

patterns for a safer job, you should always make some room for crazy, playful

ideas that won’t even make sense. You can make your own answers here.

Wearable tech interfaces represent a wide open playing

field. Have at it!

This article was originally published on Toptal

References:

http://www.toptal.com/designers/ux/the-psychology-of-wearables

About Author:

Antonio Autiero is a Software Engineer at Toptal. Antonio is a digital art director and UX designer

with experience in information architecture, brand development, and business

design. He has been working for over 10 years all around the world with amazing

clients such as Nike, Rolex, Ferrari, and more. He lives in Gubbio, Italy where

he's surrounded by beautiful countryside, and he always likes to meet nice

people.

Email: irene@toptal.com

Email: irene@toptal.com

%20in%20India.png)